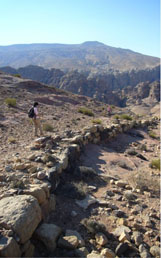

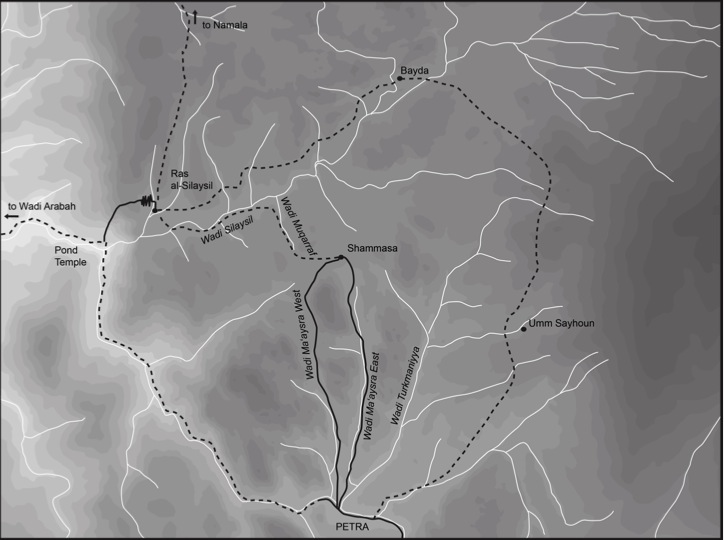

Ancient road remains south of Petra (left and right) and in Wadi Mu'aysara East (center)

About PRP

The Petra Routes Project (PRP), led by Michelle Berenfeld (Pitzer College) and Felipe Rojas (Brown University), is focused on studying traffic between the city center of Petra and its immediate surroundings. While long-range communication routes to and from this “caravan city” have been the subject of academic reflection since the early twentieth century, mid- and short-range connections have received comparatively less attention. These mid- and especially short-range connections, however, can help us understand how such a peculiar city worked in practice. While the city is perhaps best known for its long-range trade connections and cosmopolitan nature, there are many important questions about how a city in this extremely arid, mountainous landscape addressed a host practical problems (including supplying food and water to a large urban population in an arid environment) so that its population could survive and flourish. These challenges are at the heart of our investigations. How was the peculiar landscape of Petra traversed in antiquity? How did people and goods move through the city, as well as between the city and its agricultural hinterlands?

Building on our investigations of the remains of roads in the north portion of the Petra valley in 2010, the bulk of our efforts in 2011 were focused on short-range communication routes between the city center of Petra and the agricultural hinterlands to the north, and specifically on two wadis to the northwest of the city—Wadi Mu‘aysara East and Wadi Mu‘aysara West. A preliminary extensive survey revealed that these wadis were occupied and substantially adapted in antiquity. Remains of built and rock-cut roads were found in both wadis, with extensive sections of road in the middle of WMW and at least 300 meters of rock-cut road preserved at the north end of WME. Interestingly, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the roads were constructed at levels well above the wadi bed—levels on which modern donkey-riders and walkers still travel today.

In addition to roads, substantial agricultural installations, including agricultural terraces, dams, cisterns, and water channels were found throughout the wadis. Particularly interesting were “clusters” of occupation in the areas between mountains and outcroppings, sometimes high above the wadi bed. In these areas, terrace walls and dams were used to create areas for cultivation (flat, well-watered) and every possible means of collecting and managing water was used to its full advantage.

These initial investigations suggest that the city’s northwest wadis served a variety of purposes. They were not simply natural conduits, nor defenses, although they did act as both. Rather, the importance of these liminal spaces (neither entirely urban nor entirely rural) lies in their versatility. The wadis provided the most direct, although not necessarily the easiest, access to the agricultural lands to the NW of the city as well as to the steep ramps leading from the Ras As Silaysil High Place to the Pond Temple and from there to Wadi Arabah. The wadis also served as natural defenses, for they were so narrow and the cliffs lining them so steep that any intruder would almost inevitably be exposed to attack from above. Less obviously, but just as importantly, the wadis also served as an intermediate cultivation territory between the urban core and the large-scale agricultural areas to the north. They were intensively cultivated: water and soil were collected by means of fairly elaborate systems to supply sometimes surprisingly small plots of land, especially in high intra-mountainous spaces between the main wadis. The abandonment of most of this agricultural infrastructure resulted in what must be the most important change in the use of these wadis since antiquity. And yet still today, the pervasive remains of cisterns and terraces allows one to imagine what these wadis must have looked like in antiquity covered in dozens, if not hundreds, of carefully cultivated small plots of land and bustling with activity.

Home | People | PUMA | PAWS | BIV | PRP | The 2010 Season | The 2011 Season | The 2012 Season | Bibliography | JIAAW | Credits