The following text is adapted from the field report submitted to Munjazat at the end of the 2010 field season, prepared by BUPAP director, Susan E. Alcock.

The Brown University Petra Archaeological Project - 2010 Season

The first full season of the Brown University Petra Archaeological Project (BUPAP) was conducted in the Petra Archaeological Park for approximately a month long period between June 28 and July 31, 2010. The BUPAP team was composed of sixteen archaeologists and archaeology students, chiefly but not entirely from Brown University, with the assistance of seven workmen from the villages of Umm Seyhoun and Bayda. We would like to acknowledge from the outset our gratitude to the Department of Antiquities of Jordan, to Dr. Imad Hijazeen, Tahani al-Salhi, and Hyeam Twassi, as well as to all the residents of the Petra region for their kind hospitality.

During the 2010 season, the Project successfully carried out research along several lines, organized as three major, but overlapping, initiatives: PUMA (Petra Upper Market Archaeology); PAWS (Petra Area and Wadi Slaysil Survey) and MVB (Medieval Village Bayda). Individual elements included:

1) For PUMA

a. Limited excavation in the Petra Upper Market, with additional exploration of a small trench opened in 2009, and subsequent geophysical survey;

b. Exploratory survey of Upper Market area and city center, with focus on access routes and urban development;

2) For PAWS

a. Intensive regional survey in the area of Wadi Slaysil, Wadi Beqaa, and Bayda, including both artifact collection and detailed feature mapping and recording;

b. Detailed mapping of an ancient hydraulic system in the Wadi Beqaa;

3) For MVB

a. Detailed mapping of the architectural remains at the Medieval Village, at Bayda;

b. Excavation (two trenches) at the Medieval Village, at Bayda;

Finally, we assisted, in cooperation with the Department of Antiquities, with investigations at the Turkmaniyya Tomb, where two small trenches were opened and geophysical analysis subsequently carried out (a report on this work has already been submitted to the Department of Antiquities).

A brief description of each of these initiatives follows; a full report will be submitted for publication in the Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan for 2011.

PUMA: Petra Upper Market

A team under the direction of Dr. Chris Tuttle and Dr. Megan Perry returned to the area of the small trench opened by Brown University in 2009 in the northwest corner of the Upper Market. In the 2009 campaign, a broken paved floor had been discovered, two features within which suggested the possible presence of cist graves (see our report to Munjazat on the 2009 season). To investigate this possibility, we invited Dr. Perry, an archaeologist and physical anthropologist, to help reopen and expand this trench.

The features (explored as PUMA Trench A) proved instead, however, to represent an extremely interesting set of walls, floor and sections of connected water channels (one running north-south, one east-west). The channels were well-built, constructed of sandstone blocks and lined with a 2-3 cm thick layer of hydraulic cement (see Figure 1). Basic principles of hydraulic engineering can be seen in curves at the join between floors and walls, and the rounded corner where the channel bends from east to south. The direction of water flow proved interesting, with stratigraphic evidence for both an east to south movement (with water coming from the high bedrock outcrop to the east of the Upper Market), and a possible later reverse in direction.

The exposed sections of the channels were variably filled with debris, with the north-south portion of the channel especially marked by a huge deposit of large ceramic pieces (some preserving 40-50% of their original form), a small complete fine ware juglet, and many other fine ware vessels and cooking pots (PUMA Locus a10). This entire assemblage, on preliminary analysis, dates to the late second and early third century CE (as do the majority of other sherds discovered elsewhere in the channel debris). These data speak to the question of water system maintenance and abandonment, as well as changing uses of the Upper Market area as a whole. Finally, a small test probe was excavated under the paved surface to attempt to date the construction of the channel and paved floor, but this met with no success.

Geophysical surveying was undertaken across the entire area of the Upper Market by Thomas Urban, employing both electromagnetic induction survey and magnetometry. Full analysis of the results will not be available until fall 2010, but preliminary inspection (of both sets of data) suggested the presence of a strong linear anomaly of substantial size emerging in the southern central portion of the Upper Market.

PUMA and Urban Development at Petra

Two members of the team, Drs. Michelle Berenfeld and Felipe Rojas, undertook an exploratory pedestrian survey of the Petra city center; they initially studied ancient traffic flows between the colonnaded street, the so-called “upper market” and the domestic quarters of ez-Zantur. The realization that the roughly East-West colonnaded street and flanking monumental structures were traversed by multiple, but less conspicuous North-South routes led them to expand their area of research to study circulation over much of the Petra Basin, from the Moghar Annassara (the ancient village known as the “Cave of the Christians”) in the north to the so-called “Snake Monument” in the south.

This exploratory survey laid the groundwork for a synthetic study of the urban history of Petra and its surrounding landscape. This study will explore the monumentalization of the urban core and the surrounding wadis and, through a chronological analysis of monuments and infrastructure, Berenfeld and Rojas will investigate how different urban interventions—including fortifications, wadi retaining walls, quarries, terraces, and buildings—reshaped the symbolic image of the city.

PAWS: Intensive Regional Survey

Several members of the team, led by Alex Knodell and Brad Sekedat, carried out intensive surface survey in the areas of Wadi Slaysil, Wadi Beqaa and Bayda. This methodology involves careful exploration of the earth’s surface, observing and in some cases collecting artifactual material (chiefly ceramics and lithics) and mapping and recording all features (walls, cisterns, rock cuttings, etc.). A rigorous and systematic strategy was adopted, with walkers spaced 10 meters apart and with all survey unit boundaries and features assigned individual GPS points. In all, an area of 133 hectares was covered; this is the first survey in the Petra region to employ this particular regional methodology, at this level of intensity.

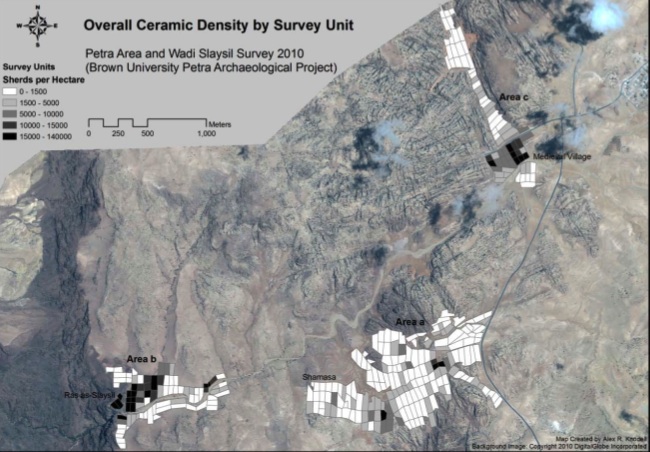

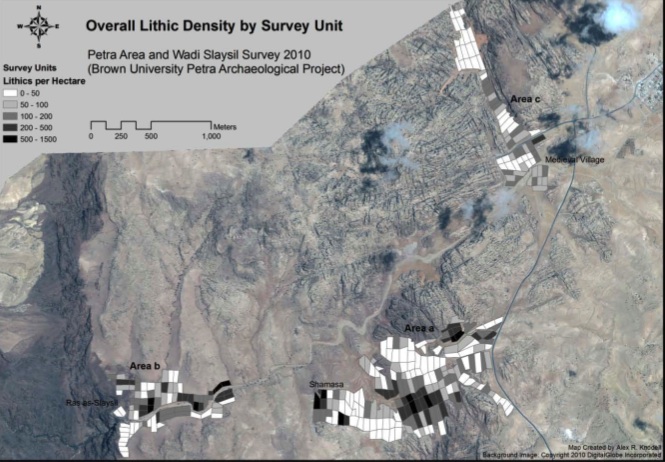

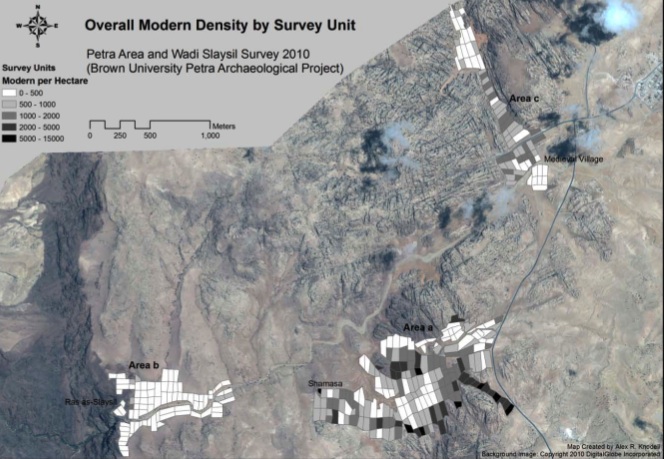

The survey team worked in three zones: the Wadi Beqaa (Area A, divided into 180 survey units, or SUs), the Wadi Slaysil (Area B, divided into 84 survey units), and across and in the vicinity of the Medieval Village, Bayda (Area C, divided into 70 survey units) (see Figure 2). In all areas, the PAWS survey proved to be extremely productive, in terms of both ceramic, lithic and feature finds. Preliminary analysis points to ceramics ranging in date from likely Iron Age to Modern, with notable concentrations in the Nabataean/Roman and Medieval (Middle to Late Islamic) periods; material of other epoch such as the Hellenistic and Byzantine era were also noted. Lithic finds were numerous, with the majority (again on preliminary inspection) dating to later prehistory (Chalcolithic onwards), but with some Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic elements as well (we would like to thank Dr. Gary Rollefson for undertaking a partial review of these finds). There appears to be spatial patterning in the distribution of ceramics, both in terms of overall density and time period (see Figure 2); for example, Area B (Wadi Slaysil) is largely dominated by material of the Nabataean/Roman era, while Area A boasts the most potential Iron Age material, and so on. Lithics too, while fairly ubiquitous, were found in distinct concentrations (see Figure 3). Finally, the survey team also observed and counted the remains of modern debris (plastic, metal, glass), which was distributed in certain predictable (if unfortunate) ways: along road sides and modern encampments, and near picnic areas for Bedouin and tourist alike (see Figure 4).

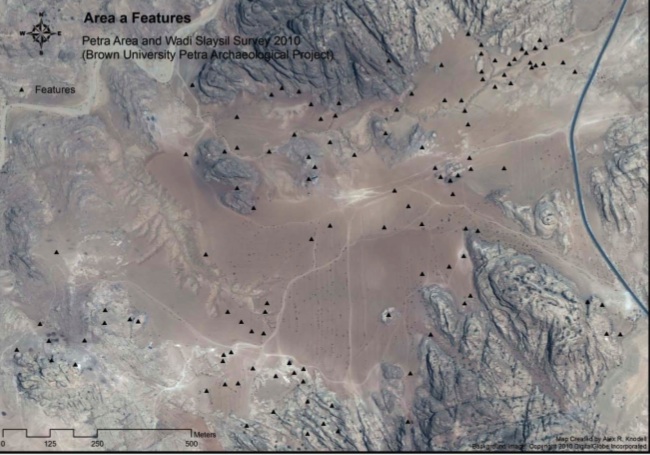

Features observed came in a range of shapes and sizes. Many were walls or wall systems, which often appeared to be terrace walls or dam structures. Rock-cut features abounded, from agricultural installations, to shrines, to quarries, to apparent water management features (cisterns, channels), to stairs, to ‘game boards’ (Figures 5, 6, 7). Again, these were distributed across the entire survey area, with 120 in Area A, 75 in Area B, and 52 in Area C (many of which in this last area had previously been documented by Dr. Patricia Bikai). Some of these features represent fascinating and sophisticated complexes of interrelated built and rock-cut elements, others are more simple and isolated: but it is clear that the land is everywhere marked and modified by past and present human activity.

While the PAWS survey did not, in 2010, seek to identify ‘sites’ per se in the landscape walked, three previously known settlements were included as part of our coverage: Shammasa (in Area A), Ras as-Slaysil (in Area B), and the Medieval Village (original name unknown, in Area C). Shammasa had previously been recorded, notably by Manfred Lindner. The BUPAP team not only surveyed the ‘Rock of Shammasa’ itself, carefully recording its ruined ‘guard tower’ and excellent views, but also documented several notable architectural remains (quarries, cisterns, a shrine and more) in the general vicinity, giving a new sense of the size and ‘structure’ of the settlement. Ras as-Slaysil too had been visited by Lindner and others. Here a detailed mapping of architectural features (with at least 24 apparent structures and many terrace walls) was undertaken in 2010 (Figure 8). Surface collection points (on preliminary results) to a fairly tightly defined period of major occupation, from the first century BCE to the second century CE, though some earlier, Hellenistic material is present, and some later finds as well. The location of Ras as-Slaysil, its documented (now badly damaged) sanctuary, and its possible role in long-distance movement through the region, makes this an exceptionally interesting area for further analysis. Finally, to complement the excavations at the Medieval Village, the survey walked the entire area of the village and recorded surface finds that can be brought into dialogue with both the architectural mapping of the area and its excavations.

PAWS: Wadi Beqaa Dam Documentation

Shortly after the PAWS survey began, a well-preserved and extensive system of hydrological features was discovered in the Wadi Beqaa, running roughly east-west from very close to the present-day Bayda-Umm Seyhoun road toward the Wadi Slaysil (Figure 9; it should be noted that we have not explored the east side of the modern road). The system’s coherence, coupled with direct and ongoing threats to its survival from annual inundation, encouraged a team (Timothy Sandiford and Emanuela Bocancea) to record it through both architectural and topographical survey. Using a Topcon total station, they generated a very detailed and sensitive map of the area; it would seem at this point that, at least for the most part, the system reflects a single period of design and implementation (if by no means of use). Especially intriguing are clear build-ups of silted sediment behind the better preserved dams, which might argue for the presence of ancient reservoirs or other successful water containment systems. A program of geological and geophysical investigation, perhaps coupled with limited excavation to determine the date of the system, could be an appealing future option, not least to add another, rural case study to the understanding of water harvesting and control in Petra and its hinterland.

MVB: Architectural Mapping

Advancing understanding of the later (Islamic era) periods of the Petra region is a chief goal for BUPAP as a whole, with work in and around the Medieval Village at Bayda the most manifest sign of that interest. The existence of a later ‘village’ near Little Petra and Neolithic Bayda had long been known, being most recently explored by Patricia Bikai with excavations in the 2000’s (resulting in, among other things, the discovery of two putatively early mosques).

It could be observed, however, from additional consideration of the mass of wall lines and rubble that the village was larger than previously thought and that its surface remains, although variable in preservation, could be reasonably traced. Using a Sokkia total station, Ian Straughn and Timothy Sandiford mapped a total area of 5.1 hectares with one architectural cluster to the west and the other, upslope, to the east, in the process identifying numerous contiguous (and a few more isolated) structures (Figure 10, 11). Important natural features, such as the bedrock formations that litter the area, also form part of the plan, though the area’s many rock-cut Nabataean elements remain to be added.

MVB: Excavation

Ceramic chronologies for the post-Byzantine periods (Early Islamic onwards) in southern Jordan badly need refinement, creating a desperate need for careful stratigraphic excavation and documentation in targeted locations. This ambition motivated the digging of two trenches at the Medieval Village: Trench A in the western part of the village, and Trench B in the eastern part. The excavation was led by Dr. Chris Tuttle and Micaela Sinibaldi, with Katherine Harrington and Harrison Stark assisting. All the medieval material from the MVB (and indeed the BUPAP project generally) will be analyzed by Micaela Sinibaldi.

The first trench opened, Trench A (4 m x 6 m), was placed in close proximity to an area excavated by Bikai in 2004. The levels recovered in Trench A are not securely dated as of yet, but likely belong to the 14th through 16th centuries CE. It is hypothesized that the trench lay within a courtyard of the complex, and several activity areas were discovered on well-defined surfaces. An oven (tabun) and spindle whorls were found associated with the same occupation surface (Figure 12, 13). From a former phase emerged a possible small pottery production zone, with evidence of raw clay, prepared materials (such as ground sandstone and limestone) for temper and traces of a small fire, of the type used in the Islamic period for firing its thick, very under-fired, pottery (Figure 14). Excavation was stopped at a clearly defined surface, and the trench backfilled. Finds, however, indicate the existence of yet an earlier phase in the area, and analysis of masonry phasing revealed that this explored phase of occupation follows the one excavated by Bikai.

The placement of Trench B, a 2 m x 2 m trench, reflected a desire for a deeper stratigraphic section into the site. Relatively limited amounts of pottery were discovered in this excavation, but the stratigraphy, showing at least three occupational phases, is clear, which will allow more detailed work on the ceramics found. Finds included a possible Islamic coin, to be cleaned and read by an expert. Trench B was also backfilled after a suitable stopping point was reached.

Figures

Figure 1: PUMA Trench A, with walls and water channel features visible (Photo Credit: Megan A. Perry)

Figure 2: GIS Map of PAWS Overall Ceramic Density by Survey Unit (Areas a, b and c)

Figure 3: GIS Map of PAWS Overall Lithic Density by Survey Unit (Areas a, b and c)

Figure 4: GIS Map of PAWS Overall Modern Density by Survey Unit (Areas a, b and c)

Figure 5: GIS Map of PAWS Area a Features

Figure 6: GIS Map of PAWS Area b Features

Figure 7: Rock-Cut Feature a31 (Photo Credit: Emanuela Bocancea)

Figure 8: Ras as-Slaysil Structures in Area b (Photo Credit: Alex R. Knodell)

Figure 9: Overview of the system of hydrological features documented in the Wadi Beqaa (Photo Credit: Ian B. Straughn)

Figure 10: Overview of Medieval Village at Bayda (Photo Credit: Timothy Sandiford)

Figure 11: Medieval Village at Bayda Total Station Survey Results (Map Credit: Timothy Sandiford)

Figure 12: MVB Trench A, excavation of tabun (Photo Credit: Katherine Harrington)

Figure 13: MVB Trench A, view of stones in tabun (Photo Credit: Katherine Harrington)

Figure 14: MVB Trench A, possible pottery workshop (Photo Credit: Micaela Sinibaldi)

Home | People | PUMA | PAWS | BIV | PRP | The 2010 Season | The 2011 Season | The 2012 Season | Bibliography | JIAAW | Credits